9 min to read

The longitude and British Empire

How solving the Longitude Problem perhaps made the British empire.

Lines of latitude and longitude began crisscrossing our worldview in ancient times. By A.D. 150, the cartographer and astronomer Ptolemy had plotted them on the twenty-seven maps of his first world atlas.

Seafarers have always needed to know their location in sea to avoid danger and ensure a successful voyage. Also, the more precise navigation could increase their speed and efficiency.

Longitude and latitude, functioning as mathematical place names. Formed a structure of names well before we narrate the human names for these places.

This meant pinpointing the ship’s longitude and latitude on a reliable map. Latitude was fairly straightforward to measure from a ship. Longitude was the problem. However, Longitude will soon become central to the stories of navigation and place discovery for the Human kind.

The Origin

Mariners were plying the oceans for centuries before the longitude ‘problem’ was fully solved. In India, we had sea-trading relationships with South-Asian and Romans. Many of these voyages were still short distances and along familiar routes. Longer voyages were risky. And, when land was out of sight, birds, marine animals and plants could reveal its proximity and direction.

Pre-Compass

One of the first and most valuable inventions in navigation was the leadline. Since the 5th century BCE, the leadline has been used to both measure the depth of the water and determine the characteristics of the sea floor. They used it for finding the depth of water near coasts.

Eclipses had long been used for observations on land, including an ambitious project of the 1570s and 1580s to fix the positions of different parts of the Spanish empire. Eclipses could not provide a routine solution in sea. Christopher Columbus made observations twice in the Caribbean, although his results were not impressive in terms of accuracy.

Before British ruled the World

Spain and Portugal were the maritime superpowers of the 15th century. In 1494, Spain and Portugal partitioned the world. Under the Treaty of Tordesillas, a line west of the Cape Verde and Azores islands split the globe from pole to pole. Lands discovered to the west of the line would belong to Spain, those to the east to Portugal. In the sixteenth century the Spanish monarchy prohibited the circulation of their maps and descriptions to protect their outposts in the Pacific. So it was a major coup when a British seaman took a book of sea charts and sailing directions from a captured Spanish ship. The charts were soon copied and made available by a London chart maker. By the end of the 17th century, Dutch, France and England were coming to dominate the oceans. The chronology of rewards for solving the longitude solutions went together with the maritime growth of these nations. And, for that most of these nations started their State-backed schools to train and license navigators engaged in long-distance trade.

The ‘longitude problem’

Britishers also started their school with the support of Isaac Newton and the astronomers John Flamsteed and Edmond Halley. These astronomers saw this as a way in which their work could have tangible public benefit and naval growth of the British Empire.

The ‘longitude problem’, as it has become known, was a technical challenge that taxed the minds of many of the influential thinkers of the Renaissance and Enlightenment and with commercial and navigational implications. It was of interest to mathematical practitioners and to watch and clock makers as well as to seamen. Galileo Galilei, Jean Dominique Cassini, Christiaan Huygens, Sir Isaac Newton, and Edmond Halley all tussle with it as a puzzle that seemed unanswered. The active quest for a solution to the problem of longitude persisted over four centuries and across the entire continent of Europe. Most crowned heads of state eventually played a part in the longitude story, notably King George III of England and King Louis XIV of France.

In 1707, the disastrous wreck on the Scillies that scuttled four warships. That naval disaster claimed the lives of nearly 2,000 sailors. It also catapulted the longitude question into the forefront of English affairs.

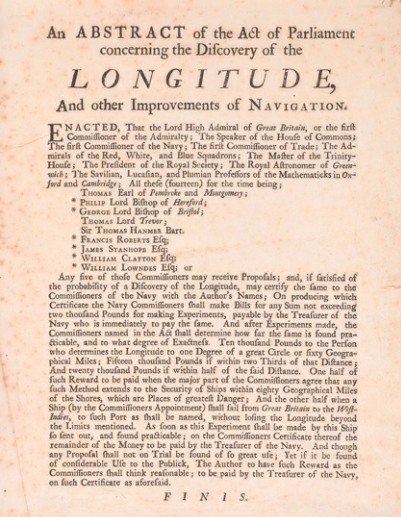

Longitude Act 1714

The Longitude Act 1714 was an Act of Parliament of the United Kingdom passed in July 1714 at the end of the reign of Queen Anne. It established the Board of Longitude and offered monetary rewards for anyone who could find a simple and practical method for the precise determination of a ship’s longitude. It also allowed for the advancement of sums up to £2000 ‘to make Experiment’ of promising schemes.

The Act was also notable in creating a diverse group of experts, the Commissioners of Longitude, who brought together Britain’s naval, political, academic and scientific interests. Sir Isaac Newton, was their advisor.

Watch vs Lunar

A clock or watch contains the time so many felt that the mechanical clock is the right contender in the effort to find longitude at sea. Galileo, who, as a young medical student, successfully applied a pendulum to the problem of taking pulses, late in life hatched plans for the first pendulum clock. In June 1637, according to Galileo’s protégé and biographer, Vincenzo Viviani, the great man described his idea for adapting the pendulum to clocks with wheelwork for assisting the navigator to determine his longitude.

The second way to determine longitude, which did not depend on knowing the time at the prime meridian. They based it on the position of the moon in the sky relative to the sun and other stars. In 1766, Nevil Maskelyne, Astronomer Royal, first published his Nautical Almanac, which provided the tables for determining longitude from lunar observation. Back in England, Newton grew impatient. He realized that any hope of settling the longitude matter lay in the stars. The lunar distance method that had been proposed several times over preceding centuries gained credence and adherents as the science of astronomy improved. Thanks to Newton’s own efforts in formulating the Universal Law of Gravitation, the moon’s motion was better understood and to some extent predictable.

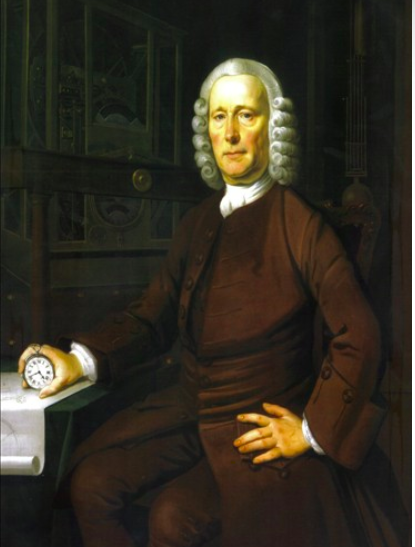

Clockmaker John Harrison

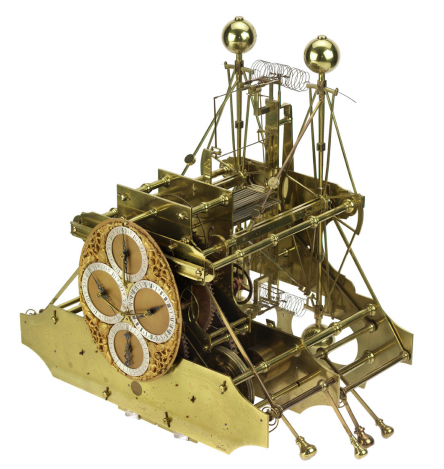

English clockmaker John Harrison, learned his father’s trade of carpentry. He will soon accomplish what Newton had feared was impossible. As, he invented a clock that would carry the accurate time from the home port, like an eternal flame, to any remote corner of the world.

English clockmaker John Harrison, learned his father’s trade of carpentry. He will soon accomplish what Newton had feared was impossible. As, he invented a clock that would carry the accurate time from the home port, like an eternal flame, to any remote corner of the world.

With no formal education or apprenticeship to any watchmaker, he constructed a series of virtually friction-free clocks that required no lubrication and no cleaning. These were made from materials impervious to rust, and that kept their moving parts perfectly balanced in relation to one another.

He did away with the pendulum, and he combined different metals inside his works in such a way that when one component expanded or contracted with changes in temperature, the other counteracted the change and kept the clock’s rate constant.

Most of his success, were dodged by members of the scientific elite who distrusted his magic box. The commissioners charged with awarding the longitude prize—Nevil Maskelyne among them—changed the contest rules whenever they saw fit, to favor the chances of astronomers over the likes of Harrison and his fellow mechanics. But the utility and accuracy of Harrison’s approach would triumph. His followers shepherded Harrison’s invention through the design modifications that enabled it to be mass produced and enjoy wide use in the British Empire.

It took decades and a king’s intervention, for him to get awarded the money. Yet even King George could not force the committee to officially acknowledge that John Harrison had solved the problem.

An aged, exhausted Harrison, ultimately claimed his rightful monetary reward in 1773—after forty struggling years of political intrigue, international warfare, academic backbiting, scientific revolution, and economic upheaval. One of the persons responsible for his fame was Captain Cook.

An aged, exhausted Harrison, ultimately claimed his rightful monetary reward in 1773—after forty struggling years of political intrigue, international warfare, academic backbiting, scientific revolution, and economic upheaval. One of the persons responsible for his fame was Captain Cook.

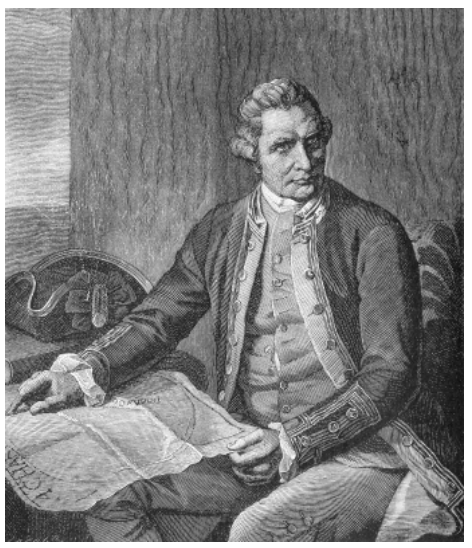

Captain Cook

Captain Cook had travelled around the world twice and was about halfway through his third voyage when he died. Building on the ability to determine longitude reliably, Cook’s voyages mark a significant shift in how Europeans could know the world. Captain Cook was the first explorer who could accurately determine longitude at sea. In Cook’s voyages, a wide assortment of instruments, from the clocks to the dipping needles, were essential for creating an accurate account of places.

Captain Cook had travelled around the world twice and was about halfway through his third voyage when he died. Building on the ability to determine longitude reliably, Cook’s voyages mark a significant shift in how Europeans could know the world. Captain Cook was the first explorer who could accurately determine longitude at sea. In Cook’s voyages, a wide assortment of instruments, from the clocks to the dipping needles, were essential for creating an accurate account of places.

In the middle of the eighteenth century, and in time for Cook’s second voyage, John Harrison developed a spring-based chronometer that could keep tolerably accurate time on a ship through a wide variety of climates. It was then possible to compare the two times and thus calculate the longitude. The more accurate the times, the more accurately the longitude would be measured. By referring to the clock when it is noon locally (i.e. the Sun is at its highest in the sky where you are) you can read, almost directly from the clock face, how far around the world you are from the leaving where you had regulated the clock.

By demonstrating the watch’s effectiveness for determining longitude, Cook helped to promote the geometrical division of space. Technological changes thus provided the basis for an ever more accurate mapping of the places of the world.

Not only does he produce numerous maps, but his ability to measure longitude gives his maps a geometrical accuracy unequalled at the time.

By demonstrating the watch’s effectiveness for determining longitude, Cook helped to promote the geometrical division of space. Technological changes thus provided the basis for an ever more accurate mapping of the places of the world.

Not only does he produce numerous maps, but his ability to measure longitude gives his maps a geometrical accuracy unequalled at the time.

Impact

Soon with the advancement in the correct measurement of Longitude more work was done with Mapping our world. Organizing a map by the grid of longitude and latitude also creates a sense of the possibilities of place. The map includes unknown regions, which helps travellers avoid surprises, or at least makes it clear where surprises could be expected. The narrative of exploration becomes an attempt to fill in blank places rather than to move further along a line. Along with that Greenwich was firmly fixed as the meridian of origin for all these measurements. British dominance in submarine cables practically reinforced its astronomical and navigational importance, allowing their connection for longitude measurements to the Continent, the Americas, and across the World.

Want to read more? Read this book