6 min to read

Newton and the bubble

What monetary policy came via his ‘‘fit of absent-mindedness"?

As a child, he spent his pocket money on tools and made a working model of a windmill. A treadmill, run by a mouse. Also, fixed a paper lantern to a kite. By, 1665 he had to return home due to Plague from Trinity College, Cambridge. And, soon he developed his law of gravity.

Next stop was: Devised laws of mechanics to explain moving bodies, then invented the differential and integral calculus (along with German philosopher Gottfried Leibniz).

Master of the Mint.

He also, made significant discoveries in optics. After astronomy, physics and mathematics, he got an exciting role, as warden of Royal Mint.

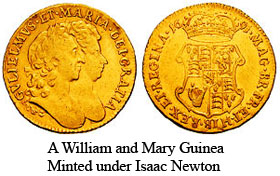

Soon he was Master of the Mint <1699>, this was generally regarded as a sinecure job. Britain’s coinage was in a shoddy state. Pound was so named, as = pound in weight of sterling silver coins. But here comes the ‘Newton as detective’. He, estimated that ~20% of the coins were FAKE.

First he suggested minting by machines to make them more uniform; they would be ‘milled’ at the edges to make them more difficult to counterfeit. But the problem remained. Paper currency was suggested. When he was asked for an opinion.

He said: “Gentlemen, in applied mathematics, you must describe your unit. Paper currency can’t be described mathematically as money”.

No one dared to argue, Treasury accepted his plan and Britain is the First Modern Nation to have Gold Standard (GS) (by 1717).

He then set the conversion rate at a level that seemed to undervalue silver. Gresham’s Law (bad money drives out good.) duly kicked in. Britons were unwilling to exchange their silver for gold at an unfavourable rate; they withheld their silver coins from circulation. Creating some troubles in the market.

Anyways, Britain was still vying with France for military leadership and with the Dutch for economic power. So, no one followed on Gold Standard at the time. And, the silver crisis did help them and made London as the primary market for Gold Trading.

In between, he was appointed by Parliament to lead a committee seeking the best way to “Discover Longitude at Sea”. He spent a few years dealing with a flood of cranky proposals. In the end, it was John Harrison (won the Cash Prize) for his chronometer, used by Captain Cook.

The battle at South sea

This was the same time when Britain was fighting with Spain, Portuguese and Dutch for the supremacy over Sea. Ambition in the Malay Archipelago had begun to shift eastwards, towards the South Seas. Britain was involved in the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714) and Spain controlled South America.

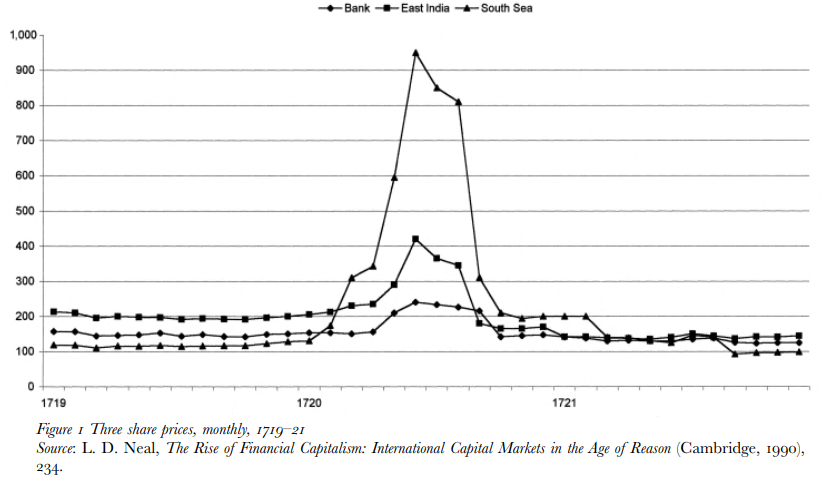

South Sea Company had been founded in 1711 with monopoly trading rights to much of South America, even though the well-established Spanish and Portuguese empires there made the region. The company was granted a monopoly to trade with South America, hence its name. At the time it was created. Its political origins, as a counterweight to the East India Company, were fundamental.

The Bubble.

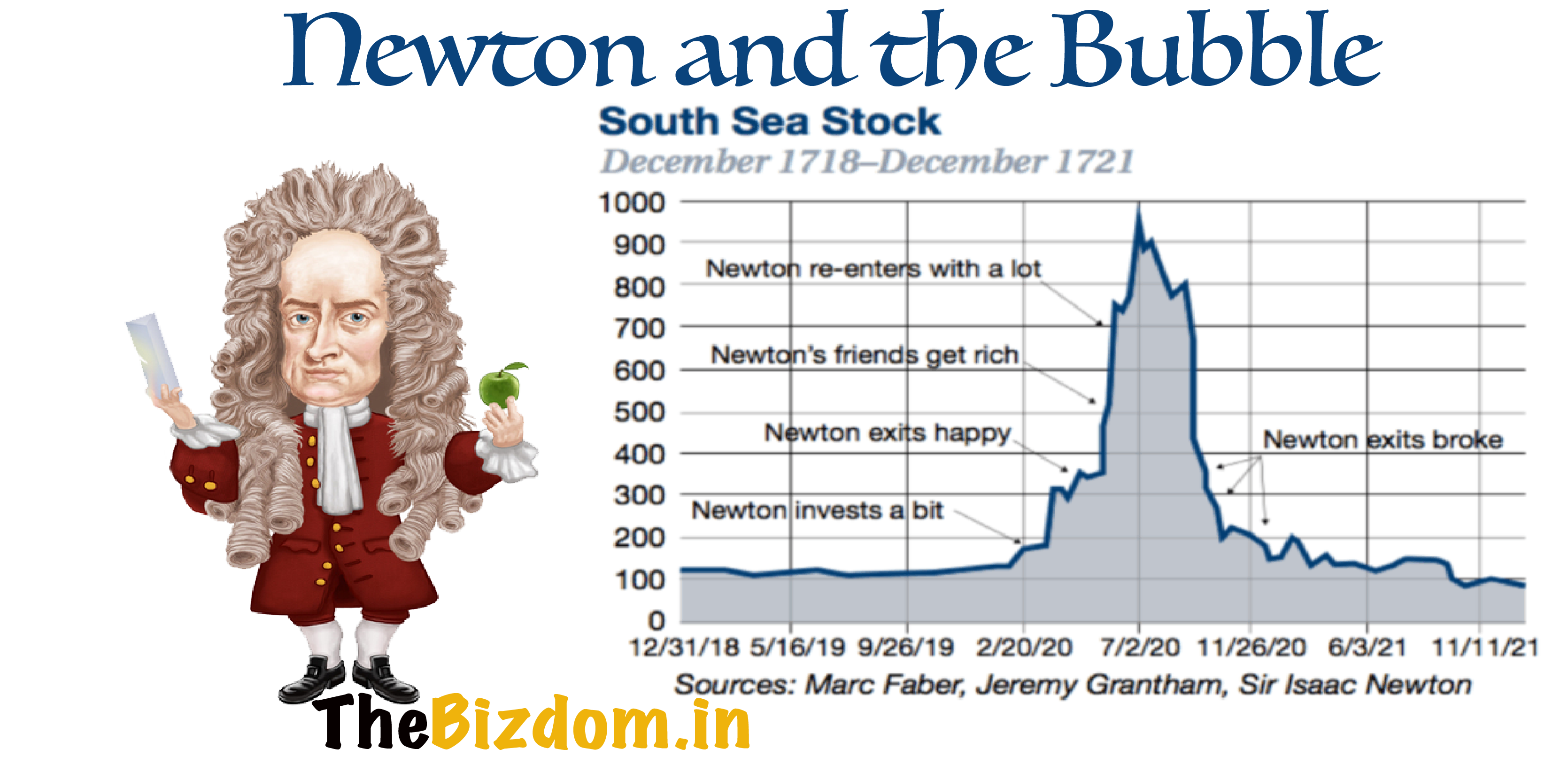

Now, he thought of leveraging his analytical skills to make money in stocks and to outperform the average broker/speculator. Prices were extremely volatile and if you could predict future price movements = make a killing. Stock in the South Sea Company especially caught his eye.

In January 1720, the company’s shares stood at 128. The following month, the company convinced the government to allow it to take over more of the national debt in exchange for its shares, beating a rival proposal from the Bank of England (afterall Bank of England was established in 1694 specifically to manage government debt). There was party politics too. The Bank was a Whig project, the South Sea Company a Tory initiative. Each operated as part of the ongoing conflicts between the parties over religion, foreign policy, the independence of Parliament, etc.

Isaac Newton, in the spring of 1720 he stated: ‘I can calculate the motions of the heavenly bodies, but not the madness of people.’ On April 20, accordingly, he sold his shares in the South Sea Company at a 100 percent profit of £7000. Later an infection from the mania gripping the world that spring and summer caused him to buy a larger number of shares near the market top. While there was NO revenue everyone was bullish about their FUTURE potential prospect of untold riches from trade (and Slaves) with the New World.

Crazy demand and fall

Investors saw the potential for massive profits through investing in South Sea Company stock so they bought it up like crazy. The demand for South Sea Company stock rose to astronomical proportions and its value quickly skyrocketed. The South Sea Company provided no physical products, nor any type of service, but there were a lot of rumors, gossip, speculation, and reputation that drove stock prices up and down.

Countless fortunes were made by those who rode the wave up and got off before the crash. Big winner (always) = big loser. As new shares issued were absurdly overvalued since most were buying for short-term profit. Now, there was NO buyers in the market.

When investors started to lose confidence in early July, prices started to slide and by September of that year the shares had collapsed to £175.

A host of other Sea-Tradin-Companies also got busted and this lead to the formation of insurance companies (Royal Exchange and London Assurance).

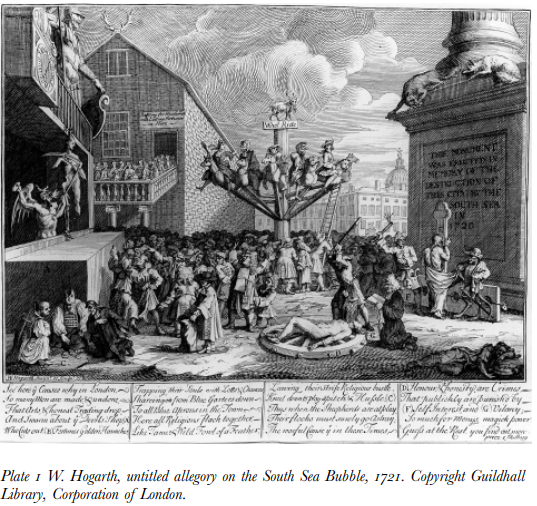

It was a classic illustration of the madness of crowds, frenzy of speculation and hype that ended in disaster.

The end.

Mercury poisoning has been suspected: traces of the metal were found in his hair. It fits with his experiments in alchemy, and could explain why he became eccentric in his old age.

In his study of the early bubbles of the 17th and 18th century, Charles Mackay (1841) said that ‘men … think in herds; it will be seen that they go mad in herds, while they recover their senses slowly, one by one’.